Campus Rec Sees Transformative Potential of Proposed Facility

16

October

2024

|

17:46 PM

America/Los_Angeles

By Brian Hiro

"; items += "

"; items += "

"; items += "

" + val['title'] + "

"; if(val['subtitle']){ items += "

" + val['subtitle'] + "

"; } items += "

"; if ((val['showpublishdate'] !== 0 && showPublishDateHeadlineSetting) || showPublishCityHeadlineSetting) { items += '

'; if (val['publishcity'] && showPublishCityHeadlineSetting) { items += '

' + val['publishcity'] + '

'; } if (val['showpublishdate'] !== 0 && showPublishDateHeadlineSetting) { items += "

"; items += "

" + date_month + "

"; items += "

" + date_day + "

,"; items += "

" + date_year + "

"; items += '

'; items += ' | '; items += '' + val['publish_time'] + ''; items += 'America/Los_Angeles'; items += '

'; items += '

'; } items += '

'; } items += "

"; items += ""; items += tags_items; items += multimedia_count; items += "

"; } }); items +="

"; if (1 > 1) { pp_jquery(".pp_blockheadlines_items-7052090").append(items); } else { pp_jquery(".pp_blockheadlines_items-7052090 .pp-headline-block").hide().css("opacity","0"); pp_jquery(".pp_blockheadlines_items-7052090").append(items); pp_jquery(".pp-headline-block:visible").animate({"opacity":"1"},300); } }); } pp_jquery(window).on('load', function() { /** * targets calcEqualHeights function (modules_v2h.js) * calculates consistent height for all visible items per block module */ pp_jquery('.pp_blockheadlines_items-7052090 .pp-headline-block').each( function() { PP_MODULES.calcEqualHeights(this); }); }); pp_jquery(document).ajaxComplete(function() { /** * when using block item nav button calcEqualHeights * function (modules_v2h.js) will be executed */ pp_jquery('.pp_blockheadlines_items-7052090 .pp-headline-block').each( function() { PP_MODULES.calcEqualHeights(this); }); });

Latest Newsroom

- Looking Back on Successes of 2025As the end of the year approaches, many are already looking ahead to 2026. But before putting the finishing touches on your list of New Year’s resolutions, let’s take a look back at some of the most-talked-about stories of 2025. Hunter Industries Gives Transformational $10M Donation for ISE Building In September, CSUSM announced a transformational $10 million philanthropic investment from Hunter Industries, one of the largest gifts in university history. The donation is supporting the construction of CSUSM’s new Hunter Hall of Science and Engineering, a cornerstone of the university’s commitment to preparing the next generation of engineers and scientists. Perfect Chemistry: Campus Wedding 16 Years in the Making If getting married at one’s place of employment seems unconventional, it shouldn’t to those who know biology professor Elinne Becket and chemistry professor Robert Iafe. The passion they have for their students is the same passion they have for the university, so it makes sense that the tied the knot on campus at the McMahan House on campus. CSUSM Kicks Off Historic $200 Million Fundraising Campaign Through the largest fundraising campaign in university history, CSUSM is aiming to raise $200 million to support student success and power the region’s future. The university officially launched its “Blueprint for the Future” campaign on Sept. 19. It’s an effort that combines philanthropy with grants and research funding. The campaign’s theme reflects both the physical growth on campus and the forward momentum building at CSUSM. Professor Elevates Samoan Language, Culture as Consultant for "Moana 2" Professor Grant Muāgututiʻa never could have dreamed that linguistics would take him to the shores of Oʻahu as he rubbed elbows with Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson and other stars of the Disney glitterati before the world premiere of the animated film “Moana 2” in 2024. Indeed, Muāgututiʻa was more than a little caught off guard when the filmmaking team behind the sequel to the wildly popular movie “Moana” from 2016 contacted him out of the blue two years ago. Construction of New Wellness and Rec Center Underway CSUSM held a Construction Kickoff on Nov. 12 to celebrate construction being underway for the Student Wellness and Recreation Center (SWRC), which is expected to open by summer 2027. CSUSM is partnering with Sea Breeze Properties – developers of North City, which includes CSUSM’s North Commons, The QUAD and the Extended Learning Building – on the SWRC, which will be the latest addition to campus life. Faith, Resilience Help Athlete Through Life-Threatening Crisis It all started with a headache. A seemingly normal ailment, but Malachi Wright doesn’t get headaches. And he definitely doesn’t get headaches that force him to leave work early or have him confined to the couch and throwing up for three straight days. That's when his mom, Ivonne Mancilla, knew this was something more. Wright spent the next 40 days in the hospital, undergoing three brain surgeries with no idea what the future would bring. But Wright defied all odds. Alumna Finds Purpose in Advocacy for Native Children and Families As Maya Goodblanket reflects on her time as a student, she vividly remembers the day she found the California Indian Culture and Sovereignty Center at Cal State San Marcos. Little did she know that she was meeting mentors that day who would help her achieve the career she has today. Goodblanket, a member of the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma, serves as an Indian Child Welfare Act court advocate for the Valley Center-based Indian Health Council, which provides health and wellness services for American Indian communities in north San Diego County. Ask the Expert: A Scientific Perspective on the L.A. Fires When the hills above Los Angeles exploded in flames early last month, Matt Rahn snapped into action. Rahn, though, isn’t a firefighter who was called into duty to help battle what became one of the biggest and most destructive fires in California history. Rather, he’s a wildfire researcher at Cal State San Marcos who, in 2019, created a unique degree program called Wildfire Science and the Urban Interface. He’s also the executive director of the Wildfire Conservancy, a nonprofit research foundation dedicated to serving the state’s firefighters and protecting its communities. Cougar Care Network Marks 10 Years as a Campus Hub for Connection Built on listening first and guiding without judgment, the Cougar Care Network enters its second decade as a trusted stop for students seeking practical help, community and a path forward. The Cougar Care Network (CCN) launched in fall 2015 as part of Cal State San Marcos’ Early Support Initiative within the Student Outreach and Referral (SOAR) program. Chronic Illness a Journey of Strength, Self-Discovery ... and Salt The first time Emmi van Zoest rode in an ambulance was in May 2024. She was in the middle of her 10:30 a.m. Communication 200 class when she realized her vision and hearing were failing. She couldn't keep her legs or arms straight and she couldn’t speak. The full memory is hazy, but she found herself sitting outside of Crash’s Market in the University Student Union with a handful of salt packets and on a Facetime call with her parents, who live in Tennessee. This experience didn’t come out of nowhere. She has postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome, or POTS, a chronic condition that she has lived with since her junior year of high school. Media Contact Eric Breier, Interim Assistant Director of Editorial and External Affairs ebreier@csusm.edu | Office: 760-750-7314

- Labor of Love: New Mom Graduating EarlyThis week, Cameron Aquino will finish her seventh and final semester at Cal State San Marcos, having graduated a semester early with a Bachelor of Arts in psychological science. Barring a disastrous outcome of her finals, she will finish as a member of the College of Humanities, Arts, Behavioral and Social Sciences dean's list in six of her seven semesters. And the one semester she didn’t earn it – fall 2024 – she was a bit preoccupied by having a baby. “And I was really close,” she said of her near-perfect dean’s list record. Aquino will walk in fall commencement at Frontwave Arena in Oceanside during the CHABSS ceremony next week, knowing that she accomplished her goals while allowing nothing to get in the way of her path. And her life journey has been winding. Born in Guam, Aquino has lived in Kentucky, Germany and California. She resided in Germany with her parents after her high school graduation before returning to the U.S. and beginning her undergraduate studies. She maintained the life of a normal college student, working and earning exceptional grades while living with her boyfriend and his family. Then came the surprise. While some students will naturally take a break – her mom was a college student when she got pregnant with her and her brother and never returned to finish her degree – Aquino was determined to not let baby Phoenix be the reason for her slowing down her journey. “Since finding out I was pregnant, I knew I wasn’t going to fall,” she said. “I knew I was going to keep going.” In fact, the preparation and ensuing birth of Phoenix, who turned 1 in November, drove Aquino to quicken her pace. To reach higher to prove to herself, her daughter and her support system that she can accomplish anything. Her near-perfect placement on the dean’s list and overall GPA of 3.67 says otherwise, but it wasn’t easy. “It was a lot of planning,” said Aquino, who commuted from Murrieta throughout her time at CSUSM. “I went through the previous semester and the whole fall semester pregnant, so I had to plan ahead for a lot of things like taking exams early and completing homework assignments early to give myself a cushion. It was a lot of planning with logistics, but I think we made it work.” After the arrival of Phoenix – Aquino wanted a unisex name for a girl just like her own – she went to school mostly in the mornings while her boyfriend attended in the evenings. Gabriel Madrigal is an accounting major who plans to graduate in May. They received help from his parents as well as friends. Aquino is also quick to point out how much CSUSM faculty has helped her in various ways. In particular, Kathie Sweeten, a lecturer who taught an infant and childhood development course while Aquino was pregnant, was influential. Lecturers Neal Dykmans (psychological science) and Melissa McGuire (history) went a long way toward providing an understanding environment. Exactly one week after giving birth, she returned to campus to take a history final. Within days of finishing her finals, she took classes in the subsequent winter session. Aquino said she derives her strength and dedication from her parents. “I get opportunities they never got to pursue higher education,” she said. “Now that she’s born, I want to provide her a better life and a better future than even I had.” Aquino plans to apply for the new Master of Science in clinical counseling psychology program that will start next fall. She has talked to psychological science professors Lisa Graves and Francisco Flores Ramirez about graduate school as she charts a course to eventually earning a Ph.D. in neuropsychology. She wants to work with military veterans. Her parents are coming from Germany to share in her celebration on Monday. Her brother had a baby just last week and he’ll be there, too. Madrigal and his family also will attend. The marking of the moment will be large, no doubt. But to Aquino, there was never an option of not finishing at the highest level she possibly could. “I feel very proud,” she said. “But I also feel like it’s doable. Life just kept throwing things at me left and right all throughout my college years. But it’s nothing you can’t get past or you can’t overcome. It’s just life, and it happens. You take it and you adapt and you do your best with it. “It’s the system of values I’ve had my whole life. No matter how hard it is, life just keeps moving. You’ve got to move along with it.” Media Contact Eric Breier, Interim Assistant Director of Editorial and External Affairs ebreier@csusm.edu | Office: 760-750-7314

- CEO’s Classroom Experience, Family Legacy Fuel $10M Gift For Hunter HallGreg Hunter never wears a suit to his abstract algebra class at Cal State San Marcos. So when he walked in dressed up one evening, his classmates teased him for being “all dolled up.” Few would guess that he is the CEO of Hunter Industries, a global organization and the largest private employer in San Marcos – or that the company is also a longtime philanthropic partner to CSUSM and is recognized on the campus founders’ seal. To them, he’s just Greg, a student who slips into class with the ease that comes from sharing four semesters with his classmates. “Greg is effortlessly humble, which is so refreshing,” fellow student Travis Bourdon said. “We knew he was a professional but had no idea of the scope. He fits right in, has made friends and encourages us to think about complex concepts differently.” A lifelong learner and Cornell University graduate, Hunter enrolled at CSUSM to challenge himself and strengthen his analytical skills. But the experience quickly became something more as he found himself inspired and motivated by the students around him. “Their grit, backgrounds and excellence impress me, as does the passion and engagement of the faculty,” Hunter said. “CSUSM is a special place with a clear commitment to advancing social mobility and student success across the region. It means a great deal to continue my family’s legacy of support.” This experience, combined with the family’s longstanding commitment to CSUSM, inspired a transformational $10 million gift to fund a new STEM facility. Recently approved by the CSU Board of Trustees, the building will be named Hunter Hall of Science and Engineering and is scheduled to open in fall 2027. Hunter Hall will boost engineering enrollment from 500 to nearly 2,000 students, strengthen the region’s workforce pipeline and support economic growth. “We are deeply grateful to the Hunter family and Hunter Industries for this extraordinary gift,” President Ellen Neufeldt said. “Greg’s experience in the classroom gives him a unique perspective on our students, many of whom are the first in their families to graduate from college. Hunter Hall will be a landmark addition to campus, providing state-of-the-art STEM facilities, fueling regional innovation and strengthening pathways for future graduates.” The Hunter family has helped shape CSUSM’s history for three generations – including Greg’s grandparents, parents and aunt, Ann Hunter-Wellborn, who served on CSUSM's University Council before the campus was founded and has continued to advocate for many student success programs. Over the years, Hunter Industries has supported several pivotal projects, including the Clarke Field House, University Student Union, Hunter Design Lab and state-of-the-art physics laboratories. The company also provides internships, mentorship and faculty support, and employs many CSUSM alumni. As for balancing coursework and running a global company, Greg approaches his studies with the same focus and dedication that define his leadership. “Greg is an exceptional student,” mathematics professor Hanson Smith said. “He even makes time for office hours, which is remarkable for someone who is also a CEO. Students are typically career-focused. Greg already has an extraordinary career, yet he’s here because he loves learning, which is likely what makes him such an effective leader.” With the Hunter gift, CSUSM’s “Blueprint for the Future” campaign – the university’s most ambitious fundraising effort – has raised nearly 80% of its $200 million goal. The campaign reflects the university’s continued growth and its commitment to advancing social mobility across the region. Explore Blueprint for the Future to see how CSUSM is different by design. Media Contact Eric Breier, Interim Assistant Director of Editorial and External Affairs ebreier@csusm.edu | Office: 760-750-7314

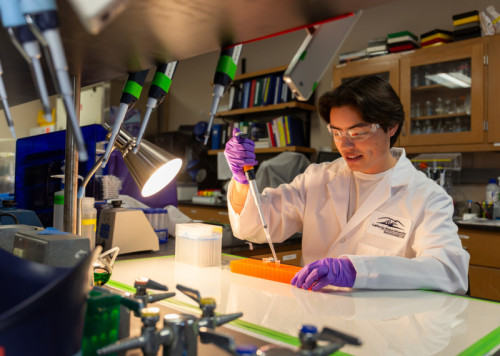

- Finding Growth Through Patience, Campus InvolvementUnlike most children, Quetzalli Johnson wasn’t afraid of visiting the dentist. When she was growing up, her mother always made dentist trips a positive experience for Johnson and her brothers by offering them rewards for doing well in the office. Those positive childhood moments led Johnson to dream of working in health care and dentistry. Today, Johnson is one step closer to fulfilling that dream. “I’m so excited. I feel like the finish line is right there,” said Johnson, a fifth-year general biology major and pre-dental student who's graduating from Cal State San Marcos this month. “I’m really excited to navigate the world outside of school, spend time with my family and husband, and start working as a dental assistant during my gap year.” Along with a gap year to gain experience, Johnson plans to move to North Carolina with her family. She hopes to attend her top choice, the University of North Carolina, to study dentistry and become a dentist. Johnson was an active member of the Pre-Dental Society at CSUSM. She joined the campus organization in spring 2024 and became the social media officer during the 2024-25 academic year. Her efforts in the club helped her achieve the role of senior president this fall. “Being a part of that club taught me a lot about confidence and allowed me to be really comfortable speaking with other students,” she said. “I loved the leadership roles because of what they brought out in myself, and I loved being able to help and support others.” Not only did the Pre-Dental Society give Johnson a place where she belonged, but it also helped her understand the path to dental school. As club president, Johnson has tried to make clear to newer members that they should take their educational journey at their own pace. She often talks about her experience as a fifth-year student and how that extra time has benefited her academically. “I feel like a lot of members think they need to graduate within a certain time, because in high school that’s what we’re told,” Johnson said. “We’re told, ‘You have to graduate college in four years,’ and sometimes that can be a little discouraging. I think it's nice for the members to hear that I’m a fifth-year and see that I’m not defeated by it. I’m enjoying the ride.” Johnson also works hard to make the Pre-Dental Society a welcoming place for students. She encourages members to ask questions, informs them about volunteer opportunities and helps them connect with academic resources and see what lies ahead on the path to dentistry. Her passion for creating and fostering a loving environment is evident to her peers and professors. James Kezos, an assistant professor of biology, has worked closely with Johnson in the classroom and lab. “She is a very determined, hard-working and compassionate individual who has set high goals for herself,” Kezos said. “She is willing to learn and help with any task, showing exceptional levels of initiative and dedication. She excels at whatever responsibilities she undertakes, including her classwork, her research and her extracurriculars such as being president of the Pre-Dental Society.” In the Fly Lab with Kezos, Johnson began studying the physiological adaptations to chronic high-sugar diets in Drosophila (fruit flies) and how these diets affect their heart health and lifespan. Johnson explained that because Drosophila share many genetic traits with humans and have such a short lifespan, they’re ideal subjects for biological study. Alongside the study on high-sugar diets, Johnson has analyzed the Hedgehog signaling pathway in Drosophila heart function. “If we’re discovering new things that could help someone else’s future research, if it could be applied in any way and help the human population, I think that’s really neat,” Johnson said. “I love that we’re taking steps forward to potentially help people. That’s what I want to do in my future, help people.” As the Fly Lab’s sole data analyst, Johnson works closely with the flies’ heartbeats – noting that, in some cases, the flies have a fluorescent heart – by watching videos and turning that information into data through programs like Microsoft Excel. “The biggest impact she has made has been her efforts in implementing a large statistical code to process and analyze our fly cardiac videos,” Kezos said. “Without her help, we would not be able to analyze any of our data, and probably would be struggling with fixing the code.” Creating the code was a challenge that Johnson felt confident in tackling. She had data analysis experience from EOS Fitness, where she worked as a data coordinator. She also took a class on biological data analysis, so when Kezos mentioned that he had code that needed fixing, Johnson was quick to take on the project. It took Johnson roughly two months to go through the nearly 3,000 lines of code. She watched thousands of videos, quantified the data and made it possible for the lab to analyze all of their hard work. Johnson referred to the project as the ultimate puzzle. “It was so frustrating but also really rewarding,” she said. “That went beyond what I thought I was capable of, and just having the belief in myself that I could achieve that, it was such a rewarding feeling. It also strengthened my confidence in myself; I am capable of doing something like that. That was super empowering for me.” Johnson has used these new skills to teach other students in the lab how to use the code to analyze data. “Quetzalli has been an integral member of my lab, and has been a tremendous help in establishing the data analysis process,” Kezos said. “Without her efforts, initiative and care, we would not be as productive as we are today.” When looking back on her time at CSUSM, Johnson said her biggest advice for future students is to get involved. Transferring from Palomar College, Johnson thought she could handle everything on her own at CSUSM. She wasn’t thinking about joining clubs or finding community. But as she delved deeper into her coursework, she realized there was much she still needed to learn about the path ahead. She first heard about the Pre-Dental Society in a Biology 101 class, and the timing felt right. She decided to go to a meeting, and the organization ended up giving her the guidance and support she hadn’t realized she was missing. “I attended a meeting and thought, ‘This is so helpful,’ ” Johnson said. “Then, while I was at these meetings, I saw this community and the relationship between officers and members. I was like, ‘I really want to be a part of this,’ which was new for me. I had never felt like that before.” Being a member of the Pre-Dental Society and volunteering with the Fly Lab helped Johnson grow as a student. The knowledge she gained from both, combined with community support, helped her see how she could give back. Johnson’s newfound desire to get involved led her to participate in events such as the Student Poster Showcase. She presented a poster on the physiological responses to chronic high-sugar diets in Drosophila, the research she had done in the Fly Lab. “Get involved, because it doesn’t hurt; it only helps. You build such a great community and you learn so much. You’re able to meet like-minded people and grow as a human being,” she said. “Enjoy the ride. Enjoy where you’re at in the moment. Enjoy the people around you. Slow down and just enjoy where you’re at.” Media Contact Eric Breier, Interim Assistant Director of Editorial and External Affairs ebreier@csusm.edu | Office: 760-750-7314

- Cancer Survivor Spreads Awareness Through LegosWhen asked why he wants to be a doctor, Cristian Alvizo would often answer, “Because I like science and I love to help people.” But there was always so much more hidden behind that answer, including a diagnosis that altered Alvizo’s entire outlook on life. It wasn’t until he met one of his colleagues and mentors in a lab at Cal State San Marcos that Alvizo realized he needed to change his answer to that question. Alvizo was diagnosed with testicular cancer the day before his high school graduation. He attended a physical required for his high school golf team that didn’t thoroughly examine for testicular cancer. After his appointment, he felt the need to self-screen, and that’s when he noticed something was off. He requested another appointment – disguising it as an HPV vaccination so his parents wouldn’t worry – where he was advised to receive an ultrasound and meet with a urologist. After a month-and-a-half of anxiously waiting, Alvizo met with Jeffrey Zeitung, a urologist at the Scripps Clinic in La Jolla, who delivered devastating news: Alvizo had testicular cancer and needed an orchiectomy, which is the removal of one or both testicles. Alvizo remembers thinking: “I'm 18, I graduate tomorrow, my mom is in the waiting room, I was just told I have testicular cancer and now I have to get an orchiectomy next week. This is a lot at once.” But Zeitung made Alvizo feel comfortable in a very uncomfortable situation, assuring him that they would get through this diagnosis together. He guided Alvizo through the process, teaching him about the disease and comforting him with the knowledge that 99% of testicular cancer patients end up fine. “Seeing how my urologist comforted me during this time made me want the privilege to be in that same position for other patients as well,” Alvizo said. “It inspired me to move down the path of becoming a physician.” Since his diagnosis, Alvizo, who is graduating from CSUSM this month with a bachelor's degree in biology and a minor in Spanish, has involved himself in numerous opportunities to further his education and spread awareness for cancer patients. His biggest contribution has been the creation of a nonprofit organization called Bricks for Change. Started by Alvizo and a few friends, Bricks for Change aims to spread awareness for all types of cancer. “You usually hear about Breast Cancer Awareness Month, which is in October, and outside of that, maybe Childhood Cancer Awareness Month in September. But you don't often hear about the other ones, so our goal is to spread awareness for the cancers of every month,” Alvizo said. The nonprofit raises money to donate Lego sets to kids in the hospital with cancer. Since the organization launched in October 2024, it have donated 550 Lego sets ($9,000 total value) between Rady Children’s Hospital in San Diego and MemorialCare Miller Children's & Women's Hospital in Long Beach. Included in every child’s Lego set is a card that allows patients to share a photo of themselves with the set they built. The pictures are posted to the Bricks for Change Instagram page and website with clearance from the hospital. Alvizo plans to continue this organization for the rest of his life and is working toward making it a 501(c)(3) nonprofit to attract the involvement of larger companies and more funding. He also hopes to build connections with more hospitals as he begins medical school. This isn’t the only advocacy Alvizo has done for cancer awareness. He is heavily involved with the Testicular Cancer Awareness Foundation and ran his first marathon to raise money for testicular cancer awareness. Since then, he has found a passion for running and has completed seven marathons and 19 half-marathons for various charities. He has been asked to speak at the American Urological Association on behalf of the Testicular Cancer Awareness Foundation. Alvizo is finishing his last semester at CSUSM, where he has been a member of professor Julie Jameson’s biology lab since he was a senior in high school. After reaching out to her via email while in high school, Alvizo was invited to join her lab, in which they studied inflammation in the skin relating to various diseases like psoriasis and obesity. Alvizo co-published two scientific papers during his time in the lab and traveled with his lab colleagues to conferences to present their findings. Alvizo is also a STEM ambassador for CSUSM's Center for Research and Engagement in STEM Education (CRESE). Every week, CRESE ambassadors visit middle and elementary schools in the region to lead after-school programs and STEM-based projects to get kids interested in science. In addition, they staff a booth every March at Super STEM Saturday, which is where Alvizo first found his love for science as a middle schooler many years ago. Clinical experience is required to apply for medical school, so Alvizo has been interning at Palomar Hospital for the last two years as a weekly hospice volunteer. He has worked on both the ICU floor and in the emergency department, checking in on patients and providing them comfort. Alvizo also is in the process of obtaining his EMT license so he can transition into a paid clinical position during his gap year before medical school applications open in June 2026. Recently, Alvizo has had the opportunity to shadow Aditya Bagrodia, a urologist researching testicular cancer tumor markers in the blood at UC San Diego, as well as urologist Ramdev Konijeti, who works closely with Alvizo’s urologist at the Scripps Clinic. “It's been a privilege to have a full-circle moment where I'm at the same cancer center, in the exact same room I was diagnosed, but now I get to see it from the other way around. It's really surreal,” Alvizo said. So now, when asked why he wants to be a doctor, Alvizo isn’t hesitant to tell his story. He is reminded of words from a former lab colleague, Alex Gonzalez, who is also a cancer survivor: “Every cancer patient has their own story. Just even hearing a diagnosis of cancer is a big deal. But you have a way of advocating that a lot of other people don't because you are young and healthy. Your interest in becoming a doctor will go a long way for spreading the word about cancer awareness.” Which is exactly what Alvizo plans to do. Media Contact Eric Breier, Interim Assistant Director of Editorial and External Affairs ebreier@csusm.edu | Office: 760-750-7314

- Youth Lego Challenge Puts Archaeology Professor in DemandFor Jon Spenard, the start of this school year was hectic beyond the typical reasons – and beyond his wildest imagination. Spenard, you see, is an archaeology professor at Cal State San Marcos, and it was in about late August that archaeologists from around the world suddenly found themselves being bombarded with attention. As Spenard can attest, that’s not the normal reality for a scholar in his field. The reason for the surprising interest in archaeology? In August, the FIRST (For Inspiration and Recognition of Science and Technology) Lego League Challenge – an international competition for elementary and middle school students that attracts almost 700,000 kids – released its annual theme: “Unearthed.” As the website states: “Every artifact we uncover holds a story. Each tool, each innovation, each work of art connects us to the people and ideas that came before us. Using STEM skills and teamwork, today we can dig deeper into discoveries than ever before.” Almost overnight, Spenard was on speed dial. “No one was expecting this,” Spenard said. “Every archaeologist and museum I know was suddenly flooded with calls and messages requesting meetings.” So it was that on the afternoon of Nov. 24, Spenard met with a FIRST Lego League team named Bikini Bottom Brick Builders – three middle school girls from Temecula and their parents – in the Social and Behavioral Sciences Building. The team was trying to build a LiDAR scanner – an acronym for “Light Detection and Ranging,” LiDAR is a remote sensing method for creating 3D models of the real world – and Spenard talked to them about how the technology works, how it relates to archaeology and how they could use their newfound knowledge to make better scans. That consulting session was the latest of about a dozen that Spenard has conducted this semester – some on campus, some by email, some at a public archaeology event that he attended in October (Arch in the Park in San Diego). “The groups and their parents do deep research,” he said. “I think many found me through our departmental website.” Each year, the FIRST Lego League introduces schoolkids to a scientific and real-world challenge that will be the focus of their research. The competition involves designing and programming robot prototypes with Legos to complete tasks, and working out a solution to a problem related to the theme. The students meet for regional, national and international tournaments to compete, compare ideas and display their robots. Spenard’s assistance to teams in the region has run the gamut, from conveying the general nature of archaeology – hint: as he says, “it’s not dinosaurs!” – to listening to presentations to providing feedback on early design prototypes. Though wholly out of the blue, the experience has been a rewarding one for him. “My hope, more than anything, is that these kids have walked away with a much better understanding of what archaeology is and how it is done,” Spenard said. “My impression is that, collectively, these kids are doing amazing engineering work that will revolutionize the field of archaeology and many others someday.” Media Contact Brian Hiro, Communications Specialist bhiro@csusm.edu | Office: 760-750-7306